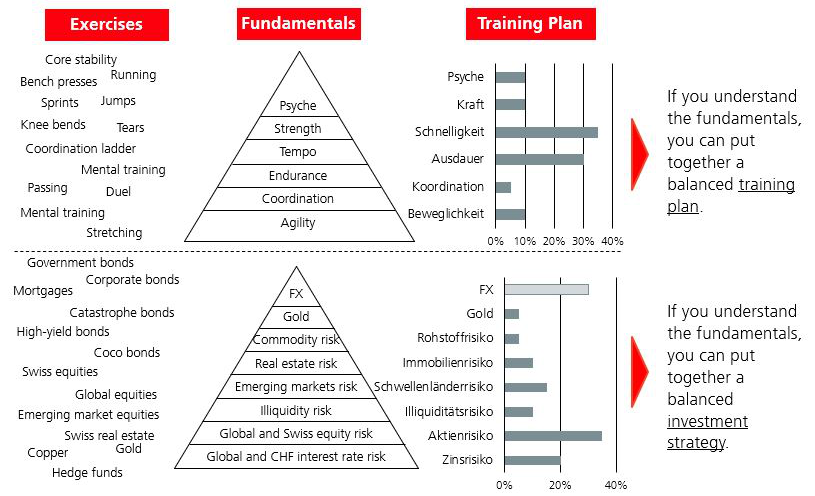

Risk model as the foundation for a balanced training plan

Those who set themselves a goal in sport need to know the fundamentals of mobility and speed. The situation is similar when investing – the first part of a three-part series on strategic asset allocation.

Text: Roger Rüegg

In strategic asset allocation (SAA), the focus is on the long-term orientation of the portfolio. Taking into account the risk capacity or a target risk, the ideal combination of possible asset classes is sought, namely the SAA, which aims for the best investment performance over the longer term.

The SAA not only accounts for a large part of the investment result – and is therefore of central importance –but also has a disciplinary effect. On the one hand, it helps to keep a cool head in times of crisis. On the other hand, it tends to reduce increased risky positions in a positive financial market environment.

In order to ensure that we always act appropriately from the perspective of investors, we focus on the key fundamentals of the investment strategy and the attendant risks in the first step of the SAA. We are convinced: if we know the fundamental components and their interactions, we can also put together a balanced investment strategy.

What are the fundamentals of an investment strategy?

In essence, it is no different than sport. Those who set themselves a goal in sport must first know their current fitness level. Determining your current level of fitness includes basics such as mobility, coordination, endurance, strength or speed. This is the basis for a balanced training plan with specific exercises.

From the fundamentals to a training plan

The same applies when investing. First, the individual risk appetite and risk capacity must be determined. Risk factors, such as interest rate, equity and illiquidity risk, serve as the basis. This lays the foundation for an optimal investment plan. Analogies to sport apply here too. Just as the optimal training plan varies depending on the type of sport and age of the athlete, the optimal investment plan should also be tailored to the investor. A younger athlete in an explosive sport places more emphasis on speed, which may correspond to a higher equity or illiquidity risk when investing. Like a training plan with exercises as a bundle of fundamentals to achieve a sporting goal, the SAA and its asset classes are a bundle of optimal risk factors for the targeted investment goal.

What are the fundamentals of each investment strategy?

We analysed the investment returns of typical multi-asset strategies for the fundamental components. This revealed that many asset classes depend on the same drivers. What's clear is that 85% of the risk of an investment strategy can be explained in three factors; and six factors account for 95%. Based on a statistical analysis, we have determined the fundamentals that can explain as much as possible of the risk of an investment strategy and the individual asset classes, with as few factors as possible and a low correlation. For example, we abstained from a credit premium because it is already covered by the equity market and illiquidity premium.

It is evident that each asset class can be characterised by the following, deeply correlated risk factors:

- Swiss interest rate risk

- Global interest rate risk

- Swiss equity market risk

- Global equity market risk

- Illiquidity risk

- Emerging markets risk

- Real estate risk

- Commodity risk

- Gold risk

We model the foreign currency risk with the effective currency allocation of the respective asset class. Despite the limitation to these nine risk factors and the foreign currency risk, more than 98% of the risk of a typical investment strategy can be explained. If we have these risk factors under control, we can create the optimal investment plan.

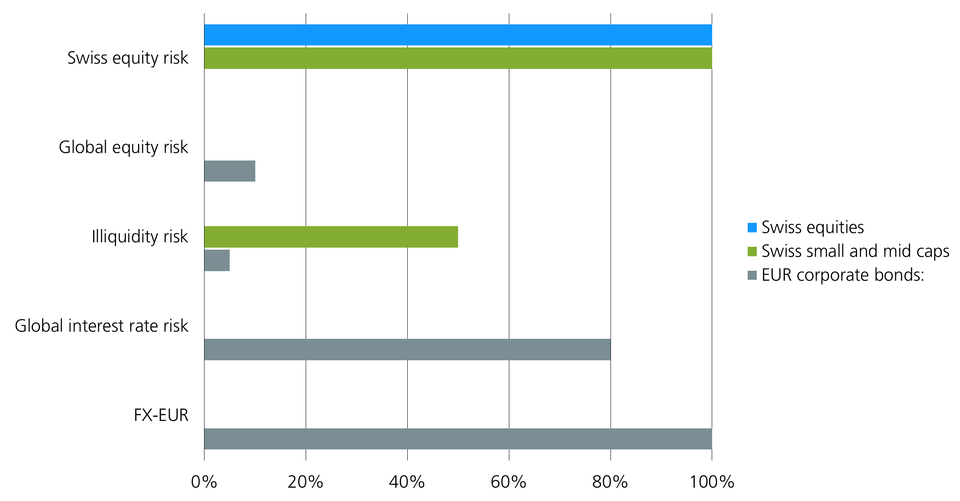

How can we see asset classes as a mix of fundamentals?

As with physical exercise, where stretching the back leg muscles, for example, is associated with promoting a fundamental aspect (mobility), there are asset classes that only have to take one risk factor into account. One example of this is the broad Swiss equity market, which is entirely subject to the Swiss equity risk factor. However, if you combine stretching the leg muscles with the standing scale on one leg, for example, the ability to coordinate is added as a second fundamental aspect. An analogy to this is the separate consideration of Swiss small and mid caps. In addition to Swiss equity risk, they also include a premium for illiquidity.

In general, it can be stated that the more complex the training exercise or asset class, the more fundamentals or risk factors are involved. For instance, European corporate bonds are not only dependent on global interest rate risk, but also have a sensitivity to illiquidity risk and global equity risk due to the additional credit risk. They are also exposed to a foreign currency risk in euros.

Allocation of risk factors to asset classes

The following fictitious example illustrates how risk changes affect asset classes: If the expected illiquidity premium, defined as the premium between MSCI World Small Cap and MSCI World Large Cap, increases by 1%, then the earnings potential of the Swiss small and mid caps, all other things being equal, will increase by 0.5% and the EUR corporate bonds by 0.05% respectively, as both investments have a positive sensitivity to the illiquidity premium.

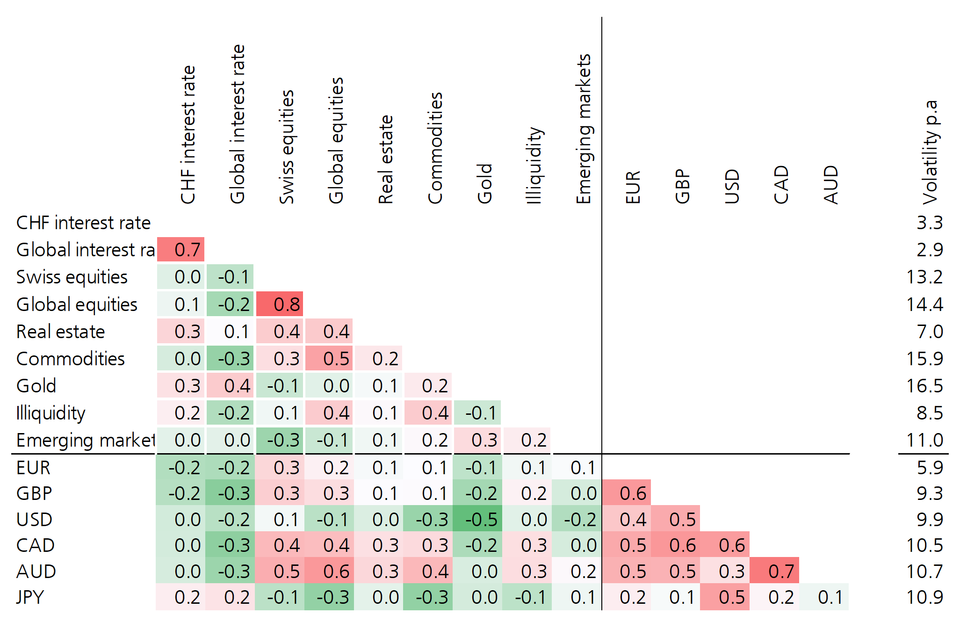

How do the defined fundamentals interact?

For the interaction of the risk factors, we show the correlation matrix we currently expect with the expected risk (volatility p.a.). Thanks to the heterogeneous selection of the fundamental factors, the correlations between the factors are low, which ensures the stability of the risk model. Only the Swiss franc, the global interest rate factor and Swiss and global equities measured in local currency are expected to be highly correlated. However, since these factors form an important part of a typical Swiss investment strategy, they are incorporated directly into our risk model.

How risk factors interact with each other

It is also possible to see why EUR, GBP, CAD and AUD are called cyclical currencies, as they have a positive correlation with the equity markets.

Benefits of a strategic factor risk model

The first advantage is that we can use a factor risk model to assign each asset class to the risk factors. This enables us to model a new asset class that has no or only a short data history with the knowledge of the premiums it contains and also to simulate their returns in the past. For example, Coco bonds are a balanced mix of global interest rate risk and equity risk in terms of construction, without having to know their history in detail. Or we can mitigate private market investments with constant earnings histories, which often do not correspond to the effective risk due to the lack of real-time valuations, thanks to the mix of a traditional liquid risk premium and an illiquidity premium. This means that they receive their desired optimum weighting and are not systematically favoured. As an example, illiquid private equity investments in our risk model are a mix of traditional equity risk and illiquidity risk.

As a second advantage, we can focus on their correlations and risks thanks to the number of limited basic factors. To illustrate this, we have a total of 105 correlations with the 15 factors, which we can clearly depict for our future expectations. For example, with 100 asset classes represented individually – we currently have 107 different asset classes in our universe – there would already be 4,950 correlations and it would therefore be impossible to determine a robust risk model tailored to our scenarios.

The third advantage lies in a better understanding of the investment strategy and its asset classes. Thanks to the focus on the fundamental components, we can see at a glance what the DNA of an investment strategy looks like. If you have considered many different asset classes, but all of them contain the same risk factors, this is immediately noticeable. This is analogous to an unbalanced training plan in which only one fundamental area is exercised. We are also able to carry out historical stress tests for the investment strategy. Often, only data from the past ten to 20 years is available for all asset classes. Our fundamental factors make considerable use of this and are able to calculate the expected losses, for example in crises such as LTCM 1998 or the bursting of the dotcom bubble at the turn of the millennium. Our factor risk model also offers the advantage of simulating future expected scenarios.

Summary: Factor risk model as the basis for the SAA

The factor risk model forms the basis for every further decision in our SAA process. A balanced investment strategy can only be determined if we know the fundamentals. In our second article in the three-part series on the SAA, you can find out how we can now determine future expectations with the broadest possible expert knowledge.